When I found my brightest student curled up in a freezing parking garage that November night, my heart shattered into a thousand pieces. But when he told me why he was there, I knew there was only one thing I could do. I’m 53 years old and have been teaching high school physics in Ohio for over 20 years. My life has always revolved around other people’s children. I’ve watched thousands of students walk through my classroom doors, teaching them about gravity and momentum, and I’ve cheered when they finally understood why objects fall at the same rate, regardless of their weight.

Each “lightbulb moment” has been my fuel — the thing that reminded me why I kept coming back to my classroom year after year. But I never had children of my own. That empty space in my life has always been the quiet echo behind my proudest days, the shadow that lingered even when everything else looked fine on the surface. My marriage ended 12 years ago, partly because we couldn’t have kids and partly because my ex-husband couldn’t handle the constant disappointment that came with each failed attempt. Those doctor visits, those hopeful test results that always turned negative — they chipped away at us until there was nothing left.

After the divorce, it was just me, my lesson plans, and the echo of my footsteps in an empty house that felt too big for one person. I thought that was my story: a dedicated teacher who poured all her maternal instincts into her students, then went home to microwave dinners and grade papers in silence. I’d made peace with it, or at least I thought I had. I convinced myself that loving my students like they were my own was enough, even when loneliness crept in late at night. Then Ethan walked into my AP Physics class.

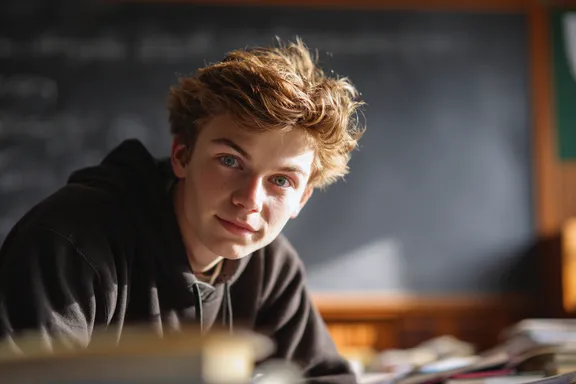

From the very first day, he was different. While other students groaned about equations and complained that physics was too hard, Ethan lit up. He would lean forward in his seat when I explained complex theories, his eyes sparkling with curiosity. “Ms. Carter,” he’d ask after class, “can you explain more about black holes? I read that time moves differently near them, but how is that possible?” Most kids his age were thinking about weekend parties or video games, but Ethan was contemplating the mysteries of the universe. He’d stay after school for hours, working through problems that weren’t even assigned. Sometimes he’d bring me articles he’d found online and ask if they were accurate, hungry to know what was real and what was speculation. I’d drive home with a smile on my face, thinking about his questions and his infectious enthusiasm.

“This boy is going to change the world,” I’d tell myself as I unlocked my front door to another quiet evening. Ethan had a way of seeing beauty in the most complex equations. While other students saw numbers and symbols, he saw poetry. He once told me that physics felt like “reading the language God wrote the universe in,” and I believed him. He understood that physics wasn’t just about formulas; it was about understanding how everything in our universe connected. During his junior year, he won the regional science fair with a project about gravitational waves. I was so proud I nearly cried during his presentation. His parents didn’t show up to the award ceremony, but I was there, clapping louder than anyone else in the auditorium. That summer, he took advanced courses online and read physics textbooks for fun.

When senior year began, I was excited to see how far he’d go. I imagined college recruiters would be fighting over him, and scholarships would pour in from everywhere. I believed the sky was the limit for a mind like his. I pictured him walking across a graduation stage with medals around his neck, already bound for greatness. But then, something changed. It started small — homework assignments turned in late, or not at all. The boy who used to arrive early to set up lab equipment began stumbling in just as the bell rang. The spark that had once been so bright was flickering, and I couldn’t understand why. Dark circles appeared under his eyes, and that vibrant energy I’d grown to love seemed to fade with each passing day.

“Ethan, is everything okay?” I asked after class. “You seem tired lately.” He’d just shrug and mumble, “I’m fine, Ms. Carter. Just senior year stress, you know?”

But I knew it wasn’t stress. I had seen stressed students before. This was something else entirely. He would put his head down on his desk during lectures, something he’d never done before. Sometimes I’d catch him staring blankly at the board like the words weren’t even registering. His brilliant questions became rare, then stopped altogether. I tried talking to him several times, but he’d always deflect with that same response: “I’m fine.” Two words that became his shield against anyone who tried to get close enough to help.

The truth was, Ethan wasn’t fine at all. And on a cold Saturday evening in November, I discovered just how far from fine he really was. That Saturday started like any other weekend. I was battling a nasty cold and realized I was out of cough syrup. The temperature had dropped below freezing, and a mix of rain and sleet was coming down hard. The kind of night where even a short walk to the mailbox feels unbearable. I really didn’t want to leave my warm house, but I knew I wouldn’t sleep without something to calm my cough. So I bundled up in my heaviest coat, telling myself it would only take ten minutes, no more.

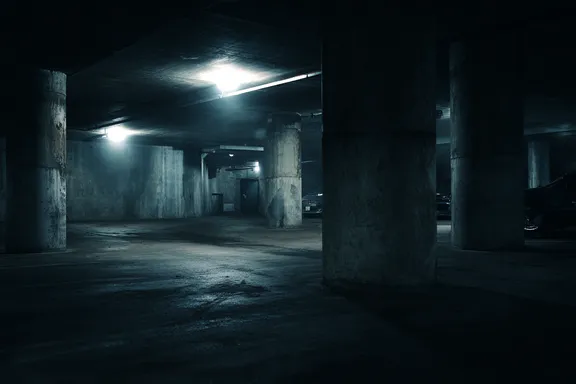

I drove to the grocery store downtown and parked on the third floor of the covered parking garage. It was one of those dimly lit places that always made me a little nervous, but at least it was dry. As I was walking toward the store entrance, something in my peripheral vision caught my attention. There was a dark shape against the far wall, tucked behind a concrete pillar. At first, I thought it might be a pile of old clothes or perhaps some homeless person’s belongings.

Then the shape moved. My heart started racing as I realized it was a person. Someone was curled up on the cold concrete floor, using what looked like a backpack as a pillow. The rational part of my mind told me to keep walking, to mind my own business.